One of the most overlooked and dramatic runs in the history of the Lamar Hunt US Open Cup occurred in 1997. That year, the San Francisco Bay Seals, who competed in the USISL’s D-3 Pro League, upset two MLS teams and the defending A-League champions to earn a spot in the Semifinals. While a Division 3 pro team reaching the final four of the US Open Cup is not unheard of (it has happened twice in the Modern Era), there was something unique about those “pros” from San Francisco.

“No one was getting paid,” said Seals starting forward Marquis White. “We were just playing for passion and pride and playing for the city.”

THE ORIGIN STORY

Tom Simpson founded the club under the name “San Francisco United Soccer Club” in 1981. The goal was to create a club that would embody everything that is great about the beautiful game and the city they represented. Also, he wanted to give his talented sons and their friends a place to play after college since there were limited soccer-playing options after graduation.

“We were the players that no one wanted,” offered Kimtai Simpson, one of Tom’s two sons. “Nobody knew who we were and we all had funny names and we had a lot of minorities.”

Tom Simpson was a standout athlete in his own right, growing up playing multiple other sports outside of soccer at a very high level. This was his first venture into the game of soccer, however. “He loves the camaraderie of a team, it was as much for him as it was for the kids,” said Kimtai.

“He loves the camaraderie of a team, it was as much for him as it was for the kids,” said Kimtai.

When Tom founded the team, he was still in medical school and coached his sons and their friends on the side. By 1985, the team had become so successful as a youth club that they began seeking opportunities to play youth opponents at an international level. The first was a trip to the 1985 Gothia Cup, one of the biggest youth tournaments in the world held annually in Gothenburg, Sweden. Then came an appearance in the renouned Milk Cup in Ireland that same season. These tournaments were the catalyst that really propelled the club to the next level.

Everything began to grow.

“We were all pretty ambitious kids,” said Kimtai Simpson. “We all dreamt about playing outside the United States.”

The club’s success attracted other players of a high caliber, building a powerhouse team in the northern Californian youth leagues, dominating many of the state tournaments.

“We inspired people to seek each other out,” mentioned Kimtai. Due to the lack of local youth competition, the team continued to travel to Europe in the summers seeking high-quality opposition. They again returned to the 1987 Gothia Cup, as well as participating in other European youth tournaments such as the Helski Cup, Dana Cup, and other Norway-based cup competitions. They also traveled to South America on a few occasions, including to Brazil where they beat Santos FC in their own stadium.

The club became so dominant that the term “super club” began to spread within the northern California youth soccer community. Many of the best players from around the Bay Area wanted to play together and thus ended up on San Francisco United.

By 1991, the club was regularly winning the Northern California State Cup as an adult men’s team. Part of this was due to participation in the highly-competitive San Francisco Soccer Football League. The SFSFL was founded in 1902 and remains the oldest continually-operating soccer league in the United States.

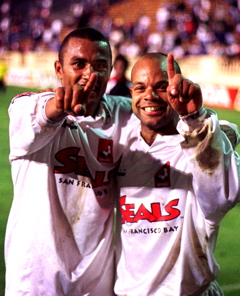

“We started playing early on against grown men,” boasted forward Marquis White, who played his college ball at the University of San Francisco before playing in the Netherlands and Bolivia. He was drafted by the New England Revolution in the 1996 MLS Inaugural Player Draft but injuries de-railed his time with the Revs and he returned to the Bay Area.

At the time, the SFSFL was arguably the highest level of men’s soccer competition anywhere in the United States and the SF United youth club could compete with any team in the league.

“The environment in San Francisco certainly produced as many players as any other projects have. If you look at the guys from the ‘96 MLS draft how many guys came from the San Francisco league, it was imbalanced to the rest of the country,” commented midfielder Troya Cowell.

“We grew up playing against Dominic Kinnear, John Doyle, Troy Dayak, Eric Wynalda. We played them in the city league here,” said Shani Simpson, Tom’s other son who now runs the current Seals’ youth academy. “They put me in my place sometimes; they went at me hard, but never to the point where I thought I couldn’t compete with them.”

“There were guys in the men’s league we played against who played in the World Cup like Bernardez of Honduras,” Kimtai noted. “These guys were huge influences on us, they inspired us. There was no pro soccer at the time so the SFSFL was the professional soccer in the country.”

In 1992, Tom made the decision to join the US Interregional Soccer League (USISL), the league that would eventually become the current United Soccer Leagues (USL). They would become one of the league’s first West Coast teams.

“The kids had been successful and if we wanted to continue to play it was the only option. We weren’t looking to go professional, we were just looking for a place for these kids to play.”

The team would be rebranded as the “All-Blacks” for their inaugural USISL season in 1992. The same team that played together as children continued to play together and began to dominate the 3rd and 4th divisions of US Soccer leading up to their 1997 US Open Cup run.

“It felt like we all grew up together,” said Shani Simpson.

“We weren’t the most talented team player-for-player, but we had been together for so long,” said forward Shane Watkins.

The team continued to seek out and play high-level competition including playing multiple scrimmages against international sides participating in the 1994 FIFA World Cup. For many member’s of the team, they felt the group could compete with just about any side in the world.

“Our international record is crazy, I mean we played against Brazil before the ’94 World Cup and we were in that game,” noted Troya Cowell. “We weren’t afraid of anyone and we had the record to back it up.”

The All-Blacks won the ‘94 Pacific Division of the USISL and the ‘95 Western Division. The club once again rebranded in 1996 becoming the San Francisco Bay Seals following a lawsuit from the New Zealand National Rugby team who are also known as the All-Blacks. That season they joined the USISL Premier, which would later become USL League Two.

They would reach the league final that year, losing to the Central Coast Road Runners (San Luis Obispo). The following season in 1997 they found themselves in the USISL D-3 Pro League, one level below the old USL-A League (Div. 2 pro).

However, they were pros in name only. None of the players were paid during that 1997 season.

“Our team was very close and they understood the difficulty of financing a professional team,” said Tom Simpson. “We became ‘professional’ just so we could play at a higher level but the guys understood that there was no money involved. Even the following year when we were in the A-League we didn’t pay the players. I just didn’t make financial sense.”

Most of the players just had other jobs, but one of the biggest ways Tom was able to help his players was to help them find work.

“I can’t tell you how many of them worked at the hospital where I was practicing,” said Tom. “I had a good connection with the parking department. The wages were decent, about $14.00 per hour back then. Our team captain, Angelo Sablo, is still there, only now he’s the boss. I got help from Russ Murphy, a contractor and youth soccer coach, who had access to properties being developed. He would allow guys to stay for free in some cases. We did a lot of stuff like that.”

FAMILY ATMOSPHERE

The team chemistry and length the guys on the team had played together were the principle reasons for their success.

“We were a fearless, underestimated family,” expressed Kimtai.

“We had great chemistry on and off the field, that had a lot to do with our success,” said Shane Watkins.

The team had a true family atmosphere and feeling about it. A lot of that had to do with the man in charge, Tom Simpson.

“Tom is a super gifted, intelligent man, he can do anything, he filled a father roll for most of us,” added Watkins. This was true to the point that the Simpsons often took in players to stay with them who were on that team.

“A lot of it was about this family aspect that had been built over the years. Tom was always looking after guys, even letting them stay at his house. He mentored us as young men and gave us a space to continue to play soccer some how,” Troya reminisced.

Shane Watkins, being one of them, lived with the Simpsons for three years claiming, “I was kind of an adopted son of Tom.”

Another Seals’ player, Chris Davini did as well.

“Chris Davini came to live with us and my dad was this guy always hugging him,” said Kimtai. “My father is very generous with his time. Sometimes as a kid I felt he loved these guys more than me. He was a lot harder on me and my brother .”

“My dad is Italian-Irish so he’s always been about family and about welcoming people. If someone needed some help both my mom and my dad were the type of people who were more than willing to help out. It was something that was part of the Seals’ culture. We had BBQ’s at Angelo’s (the team captain) house and my dad’s house, and the whole team would be there and we still do that today,” said Shani.

“You had to be honest about your commitment to the group. That’s why the group stayed pretty consistent over the years,” Troya Cowell agreed. “We all stay in touch pretty well, and it would never be hard to reconnect. It’s like no time has passed,” Shane Watkins summed up the relationship.

The practices were also very intense, with many players claiming that the practices were more intense than any game they ever played in.

“It was 5 to a side free-forming creative soccer,” Kimtai remembered.

Most of the players claim that was some of the top training atmospheres in the city.

“It was the best place to go train in a really competitive environment,” Troya Colwell said. “At that time there wasn’t much of an outlook if you weren’t going to play for the National Team. I pursued the best place in town to play soccer and that was with the All-Blacks at the time,”

“In practice we hated losing, we talked trash cause it was competitive, but we were always fighting for each other,” said Marquis White.

“You had to love to play together. It wasn’t about where we were going to go. We used to kill each other in practice. You couldn’t do anything to us in a game that we hadn’t done to each other on a terrible field, in the fog in San Francisco. We didn’t have this fear about not getting to the next level of our careers; we just really enjoyed training together day-in and day-out. None of us were thinking we could go to MLS… it was just for the joy of it,” said Cowell.

“Practices were so intense with a lot of good natured trash talk. We did enjoy it more than the game. There was so much trash talk and taunting. We’d bring a broom to practice cause we were going to sweep. It was heated, we get angry in practice, but afterward we were all good,” said Shane Watkins.

“My happiest moment wasn’t the Open Cup run, it was when I got to play with those guys from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. ,” added Kimtai.

THE OPEN CUP RUN

The family atmosphere and intense training sessions contributed to the incredible Open Cup run by the Seals in 1997. That, along with the fact that Tom Simpson highlighted making a deep run and potentially winning the tournament before the first match ever took place, primed the team for success.

“I remember when we first started qualifying that year, Tom was adamant on making an Open Cup run. He put a lot of energy into it. Tom made it a priority,” said Shane Watkins.

At the same time however, the USISL season did not begin in a dominant fashion like the Seals had become used to. Despite only losing two games in league heading into the Open Cup competition was growing. Scores were less one sided and the West Division table was tight. This led to Tom changing the system in what he believes to be one of the keys to the success of the 1997 season.

“I had been talking with the guys for a few years about changing the style of play,” Simpson explained. “This was a time when using a sweeper was the standard of play and I wasn’t much of a supporter of that style of soccer. I wanted to play with four at the back and more of a zone defense. CJ and Tim Weaver (the starting center backs) were the key elements to this switch. I asked them to try it for one weekend and they won both games that weekend. I then asked if we can stay with it and we went on a run to win 17 games in a row, including all of the Open Cup matches. It was that change in the system of play that really triggered that run and the guys really grabbed onto it. They thought they were unbeatable. To my knowledge, the system hadn’t been used in the States, but after watching Brazil in the 1994 World Cup I became convinced that it was a viable system of play with the right players.”

The D-3 Pro League used regular season games to determine which teams would represent the league in the 1997 US Open Cup. Each team in the West Division would have two road games and two home games selected to double as qualifiers. The top team in each division and the top two second place teams league-wide would punch their ticket to the tournament. After a 3-1 win over the Los Angeles Fireballs and a 4-0 win over the Chico Rooks, the Seals were off to a positive start. The deciding win ended up being a 2-1 extra time win over the Sacramento Scorpions. The Seals fell 3-1 to the Stanislaus County Cruisers, but San Francisco had done enough to finish top of the table. With a 3-1-0 record, they would win the tiebreaker with the Rooks and the Cruisers.

In the first round proper of the tournament, the Seals took on US Adult Soccer Association side and Western Amateur Champions, Inter SC, from the San Jose, California area in a match that was played at De Anza College in Cupertino, Calif. The Seals won quite comfortably, 4-0, with a brace from both the eventual tournament’s Golden Boot winner Marquis White and from Mike Black a player who would go onto only make one more appearance for the Seals in the 1997 Open Cup.

Shani Simpson recalls the dominance of captain Angelo Sabo in that game and the opposing coach saying about Angelo’s play during the match: “Can someone fucking stop that guy, the fuck!” The advanced the Seals, who would go up against a pro side in the next round.

HISTORIAN NOTE: Our historical records for that San Francisco Bay Seals vs. Inter SC game are incomplete. If anyone might be able to help us confirm any match details about that game, please CONTACT US HERE. All we have are that Marquis White and Mike Black scored two goals each and we have most of the starting lineup for both teams put together.

“After that game we realized now it was on,” said Shani Simpson. The referee that night was Brian Hall who would later referee games at the FIFA World Cup and spent time as the director of referees for CONCACAF. His role in this tournament for the Seals would become magnified in the later rounds.

In the next round, the Seals would be drawn at home in historic Negoesco Stadium on the campus of the University of San Francisco. There they would host the defending A-League champion Seattle Sounders. The Seals would upset the Sounders by a score of 1-0 in front of more than 600 fans. Marquis White scored his third goal of the tournament off of a beautiful feed from Troya Cowell.

“We really wanted to play an MLS team,” Shani Simpson recalls, noting just how important the result was.

While the first two rounds were important, the magic of the Cup for the Seals really began in the Third Round when they hosted the Kansas City Wizards at Negoesco Field. Once again Marquis White would open up the scoring inside of one minute off a ball over the top from midfielder Chris Davini to give the Seals the early lead and send the more than 1,400 fans at Negoesco that night into a frenzy. The Wizards would respond in the 40th minute with a goal from Frank Klopas, a player who played for the US National team just two years prior.

Klopas was just one of the well-known US soccer names on the pitch for KC that day. Other standout players for the Wizards included the 1997 MLS MVP Preki. The Wizards also featured Mo Johnston, a Scottish national team player.

Despite the strong Kansas City side, Marquis White would once again give the Seals the lead in the 59th minute off another fine assist from Davini. The 2-1 scoreline would be how the match ended, with the Seals pulling off another “cupset.”

Following the match, in the post game interview, Marquis White who in the previous season played in MLS before returning to the Seals, did not shy away from the confidence he had in himself and his team saying, “I felt we had a good chance because I felt we matched up well against their defenders and we just played with a lot of heart and that’s what beat them today.” He upped the ante saying, “We are going to win the next one, we are going all the way.”

“Beating the Seattle Sounders was fun, but beating KC was out of this world,” said Kimtai. “When you play against Mo Johnson and then you beat Mo Johnson when you are not expected to … all that hard work we had put in on our part paid off. Mo Johnston acted like this was a joke and he didn’t even care, in my opinion.”

This was also the first match where famous Belgium player turned scout Jean-Marie Pfaff showed up to watch the Seals hidden talents.

“Jean-Marie Pfaff would have never noticed us he showed up to the KC game,” Troya Cowell pointed out.

While beating KC at home was a huge win in the club’s history, it wasn’t anything compared to the next round when the Seals where matched up against local MLS rivals, the San Jose Clash, in a match up just down the road at Spartan Stadium in front of an announced crowd of 4,237 fans.

“That was a local rivalry whether the Clash knew it or not,” said Troya. “We felt like that was a big rival,” Shane Watkins recalled.

The end of this match is considered by some to be the greatest 17 minutes in San Francisco soccer history.

The Clash would field basically a first team line-up that night at home apart from US National Team forward Eric Wynalda, who did not play. The Clash fielded some of the best players MLS had to offer, like John Doyle, Dominic Kinnear, Ronald Cerritos and Eddie Lewis to name a few. Ronald Cerritos would open up the scoring in the 20th minute from the penalty spot to give the Clash the lead. The Seals battled hard for an equalizer that eventually came off the foot of Shani Simpson in the 77th minute.

“The ball just popped out and it hit me in the chest and someone said kick it and so I kicked it,” said Shani about the equalizing goal in his post match interview. “It was probably the most amazing feeling I’ve ever had.”

Then in the 86th minute, Shane Watkins would pick the pocket of John Doyle and beat the keeper to give the Seals the 2-1 lead late in the match. Shane said in his post match interview that “I just pressured … I knew I could pick him, I was talking about picking him all week.”

He then went on to reiterate what Marquis had said in the previous round, “We are going all the way.”

To most, this was the key win of the 1997 Cup run because it was guys that had grown up playing in the local leagues and it was the local MLS side that did not take any of the Seals players.

“It just shows, there are a lot of players in San Francisco, and basically our team that have been overlooked,” pronounced Shani Simpson in the post game interview. “That moment definitely stands out . I don’t even know how I got there. When athletes talk about being in the zone and everything just slows down, I was in that zone. I took the ball from John Doyle and I just thought I could. He’s a great player, but we didn’t feel like the gap was that big and I knew I was playing against a national team guy, but I just wanted to prove myself.”

Shane Watkins agreed years later. “The game against the Clash I think sums us up. It was pretty scrappy both ways and if any outsider looked at that game you couldn’t tell who was in the MLS and who was the other team,” said Troya Cowell.

“The only time anyone took us seriously is when we played D.C. United. I don’t think San Jose and Kansas City took us seriously at all,” Kimtai Simpson added. “

We knew the other teams would underestimate us. These guys had no idea how hard we were going to come at them,” said Shani Simpson.

The win against their local rivals set up a Semifinal match with what many considered to be the greatest MLS team of all-time. In the first two seasons of MLS (1996-1997), Bruce Arena and assistant coach Bob Bradley had led D.C. United to an MLS Cup title in 1996 and gotten even better in 1997, winning the MLS Supporters’ Shield and a second straight MLS Cup.

“That was the best MLS team of all time,” said Troya.

The defending MLS Cup champions were taking the Seals seriously, playing a complete first choice starting 11 that included John Harkes, Jaime Moreno, Marco Etcheverry, Tony Sanneh and Scott Garlick. Even still, the Seals felt like “… we were going to beat D.C.,” insisted Kimtai.

The game took place at University of the Pacific in Stockton, Calif. in front of 3,470 fans. Most Seals players who played in that game felt like they weren’t given a fair chance by Brian Hall, the referee on that night.

“D.C. United beat us, but we don’t believe they beat us … we left the field saying sometimes teams get lucky,” said Tom Simpson. “They got a gift PK in the first few seconds of the game and they won 2-1. As far as we were concerned we dominated the game and the statistics supported that. They really struggled in that game and in my mind they were lucky.”

“I don’t know if there was an biased referee in that game,” said Troya Cowell. “The penalty call was dubious, like right away. When a referee calls a penalty like that early on in a game it’s ‘cause he’s part of US Soccer. No ref should shape a semifinal with a penalty call 5 minutes into the game. If it’s gray, you just take it on your shoulders and don’t call a penalty five minutes into the game. It was a really soft call.”

“I felt it was Marco Etcheverry getting the celebrity call,” said Shane Watkins. “The big dogs are going to get the calls. CJ Brown was so adamant that he didn’t touch him and CJ is usually the silent giant, never really said anything or talked too much in training. He is a clean, honest defender. All I remember was feeling we got robbed in that game.”

Shani Simpson commented, “That was the only time I ever heard my dad question the referee. I’m suspicious of what Brian Hall was doing in that game. Etcheverry was known to flop. Nine times out of 10 no one ever calls . For one, it was early in the game. I had a one-on-one and got taken down in the box and I’m not one to dive and we didn’t get a PK. To this day I think something was happening, I don’t know if MLS said something. If we would have won and D.C. complain, maybe he’s not the top ref and not so coincidentally he was doing World Cup games soon after. It might have been a political move on his part. It would have been a great story, but not for MLS.”

“I think the MLS was very afraid of losing credibility, and I think they directed the referee to call it as tight as possible,” said Kimtai. “That’s the way I feel. That’s not to say D.C. United wasn’t an incredible team. The penalty early in the game just wasn’t a penalty. It happened in the Clash game as well.”

“It was suspect. It was way too early, I don’t even know if it was in the box,” said Marquis White. “A lot of things went on in that game that were a bit curious.”

Jaime Moreno would go on to score that penalty in the second minute of the match before Raul Diaz Arce would add another for DC United off a great run from Moreno to make the score 2-0 in the 62nd minute.

“They had elite players. Jamie Moreno set up the goal that won the game for them and you got to tip your hat to him,” said Tom Simpson about the second goal.

Marquis White would pull a goal back late in the match to extend his Golden Boot lead in the tournament with his sixth goal of the competition.

“We all felt that Marquis was a proven goalscorer who should have been on the National Team” said Shane Watkins.

The one goal was not good enough in the end as the Seals fell by a score of 2-1.

“Bruce said afterward … The Seals team was emotionally better than us and he recognized that,” said Shane Watkins.

“John Harkes, I had played against being from New Jersey, so that match up mattered to me,” said Cowell about the match. “He was a little bit of a prick that game, trying to speak with a British accent.”

“John Harkes still talks about us, like who are these kids from San Francisco,” said Marquis White.

While the run had come to an end, the Seals players still were able to see the positives in the amazing amateur run they had made.

“The run with the Seals was the highlight of my career,” said Shane with fondness. “It effects soccer history in some small way,” said Kimtai. “The ‘97 Seals team was the culmination of who my dad is and who the Seals are. A bunch kids who were left over from the Vikings team,” said Shani.

“It was an incredible time,” said Marquis White.

Unique: The Swagger / The Street Ball Artist / The Ajax Approach / Completely SF

The Seals are a unique team to soccer in this country in more ways than one. They had American basketball / football style swagger and were one of the few street-ball style teams in the history of the game domestically. They were also built using a different approach than most US clubs, because they played the local youth kids together against the men.

“We had the Ajax approach,” said Troya Cowell. “You play your youth players and they will mature. We don’t profile the talent of 18-22 year olds in this country.”

Shani Simpson believes that it is something missing in today’s game because most clubs main “ …objective is to generate revenue instead of develop players.”

“Get those young kids on the field, you’re going to lose some games but let’s get them in these games, play the youngsters,” preached Marquis White about his approach to his coaching style today. Shane Watkins believes that “you are skipping steps” by bringing in pros from all around instead of growing local talent.

Due to the years playing together the team had a confidence in themselves and their abilities. This was highlighted by both Marquis White’s postgame interview after the KC game and Shane Watkins’ interview after the San Jose game. It was a big part of this team having just the right amount of ego without being cocky and it’s still something they maintain today.

“We really did believe . We really believed in one another, especially collectively. I knew I wasn’t the greatest player, but felt that in that group together with those guys we could get it done,” said Shane Watkins before going on to say, “We were a group of players that all thought we should have been selected for one of the MLS teams when that league started. We always had something to prove against the MLS teams. There wasn’t a big difference except 1 or 2 star players the MLS teams had.”

“We were all pretty confident in our abilities,” Kimtai Simpson said. “That entire team could have played in the MLS.” While Shani Simpson continued, “The years of playing together . We knew on a national level that we were a strong team. I don’t know if it was confidence or ignorance, or if it was a solid foundation of belief. Marquis was the vocal leader saying we are going to beat these guys. Me and Angelo were more the philosophical leaders when we spoke and said, you know what, bring on the US national team, bring on Barcelona. We weren’t scared of no MLS team.”

The Seals were also one of the last manifestations of a more street-ball style, something that has led to the great success of players such as Maradona and Pele.

“That was a team of artist. We were a synthesis of styles. There are no street ballers anymore, that’s what we were. We were one of the last vestiges of street ball in the United States. You learn to play soccer now after school with a coach. We weren’t like that,” Kimtai Simpson reminisced.

Many of the players on that team would get together in the years following to play pick up games in the winter in the North Bay Area. Some even dubbed the meetings “The Rucker of Marin.”

“The most enjoyable soccer I’ve played since was in the winters when we played at Marin Academy,” Troya Cowell said. “If there was a game like that tomorrow I’d fly out.”

The 1997 Seals were a completely original team in terms of personalities and diversity, and they represented the city of San Francisco better than any other team possibly could.

“It was a homegrown team,” said Marquis White. “You got to have base, we had a base. You got to have local people.”

“The Seals were similar to the SF mentality we have all our diverse weird quirky people,” claimed Shani Simpson. “Six of the starters were African Americans. Back then it wasn’t something you saw a lot, and people thought we were a basketball team. The Seals were a multicultural team with a strong African American presence. It was a really good representation of the melting pot that is San Francisco.”

Most of the players also felt they had a player that represented the hippy culture in SF in Troya Cowell.

“I use to come out barefoot to practice at USF,” noted Troya.

The fans even had a song for other players that had long hair like Troya’s on opposing teams. “There is only one ponytail, so cut your hair, cut your hair.” Troya continued to say, “That team is forever part of our identity as soccer players.”

“Our team was built over years in that city. Me and my brother, we grew up in San Francisco, we could walk through and name the entire fan base,” added Kimtai. “It was a team with deep ties to The City.”

NEGOESCO FIELD

The atmosphere the Seals created is something that, at the time, had not yet been seen in The City and has arguably not yet been replicated in the more than 20 years since. Marquis White remarked “I just love when we were at USF playing, it was packed, it was foggy. The environment we had there had so many people. The Ultras came and connected with us and they believed in us. People had to see what the Seals were all about. USF was tiny and it was packed.”

Shane Watkins claimed, “That stadium was perfect if you get just 500 people in there, it was loud. We had the Seals hooligans, this group that started supporting us. They had a song about Marquis or one making fun of Preki when he didn’t make that National team. They were fanatical.”

Shani Simpson believed that the fans “… had a lot to do with creating a lively atmosphere. We would hang out with the fans drink beers with them and sing songs that they were singing at the game with them. We just had an open and welcoming team.”

THE 1997 LINEUP

The team during the Cup run for the most part set up with the same starting XI. Outside of the Inter SC game, the Seals put out the same starting lineup in the four matches with the four professional sides they faced. The team played a 4-2-2-2 or a version of a 4-4-2.

The key to this formation was the center back pairing of CJ Brown and Tim Weaver. CJ Brown would be selected first overall the following season in the MLS supplemental draft by the expansion Chicago Fire. CJ played the rest of his career for the Fire retiring in 2010 as the captain of the Club. CJ is currently an assistant coach with the Fire. His center back partner, Tim Weaver, was selected third overall in that same draft by the San Jose Clash, where he played for two seasons before returning to the Seals in 2000.

The keeper for the Seals in 1997 was JJ Wozniak. He had the top goals against average USISL league play that season due to his own ability and the tremendous backline in front of him.

The outside backs were Shani Simpson, the team’s second leading points getter in the 1997 Open Cup on the left side, and the team’s captain, Angelo Sabo, on the right side. Shani currently runs the Seals youth academy that still exists today. In front of them were Robert Gallow, the more defensive minded center midfielder, and Chris Davini, the man who often set up the goals for Marquis White in the ’97 Cup.

The two other more attacking midfielders were Troya Cowell and Kenny Folan. Troya would go on to play in Belgium and is currently coaching in the Maryland area. While Kimtai Simpson was not a starter, he was the first man off the bench in most games and was considered the teams “super sub”.

Up top were Shane Watkins and Marquis White. Marquis was the more attacking minded of the two, while Shane was seen as the playmaker. Marquis was part of the inaugural New England Revolution MLS squad in 1996 before returning to the Seals for the 1997 Season. He, like Weaver and Brown, was taken in the 1998 MLS draft fourth overall by the Colorado Rapids, meaning the Seals had three of the top four players taken in the MLS supplemental draft that year. He now coaches in the East Bay Area and has helped mentor players like Chris Wondolowski.

Shane Watkins was running his own currently runs his own Seals academy in Southern California, which he created because of what the Seals had meant to him. Many members of that Seals team are still involved with soccer and coaching the game locally.

“I absolutely enjoyed playing with this team more than any other group I was a part of,” said Troya Cowell. “I never would have gotten to Europe without the Seals.” Shane Watkins commented that, “I had a youth club in LA called the Seals. I called it that because that was one of the most important parts of my career.”

Tom Simpson was also named 1997 USISL Coach of the Year for all the success the team had that year.

UNBELIEVABLE SUCCESS LEADS TO HEARTBREAKING DOWNFALL

The Seals tremendous success led to a move up a division to the A-League, the second division of professional soccer in the US at the time, a move that the club might not have truly been ready for.

However, it was not as if the USSF was looking out for a club like the Seals, who had developed their entire squad from local youth players. The move up to division two was somewhat of a forced move on the part of the USL, due to the Seals own high caliber of play and success both on and off the field. The move also forced the club into a venue change from Negoesco Field to Kezar Stadium due to venue size. Kezar, while historic, is a venue considered by many in the SF soccer community to be somewhat of a “black hole” for professional soccer in the city.

The stadium’s most recent victim was the San Francisco Deltas, the team that famously won the second division North American Soccer League during it’s inaugural 2017 season before folding a week later.

The following season, the Seals returned just two starters from that ‘97 team. Only Shani Simpson and JJ Wosniak from the first choice 11 returned to the field for the Seals in their inaugural A-League season.

“That’s when the reality in soccer sort of slapped us in the face. This country isn’t ready for us. They just stripped all of our players from us. We got nothing in return and they wanted us to move up as well. It’s a little bitter sweet in terms of the story because if this had happened in Europe our team would have been rewarded for our efforts. That was disheartening to go as far as we did, and realize hey this country isn’t ready for soccer. No one was out there trying to protect us,” said Simpson.

“We felt if we could keep that team together and move into MLS, we could have been contenders,” said Watkins.

The Seals developed quite a large number of players for MLS and basically got nothing in return.

“My dad and his friends had to pay for everything,” said Shani Simpson.

The Seals produced Brandon Cavitt (28th overall MLS college draft) and Marquis White (35th overall inaugural player draft) for MLS in 1996, Albertin Montoya (4th overall MLS college draft) and Chris McDonald (24th overall college draft) went to the MLS from the Seals in 1997 and in 1998. They lost CJ Brown (1st overall supplemental draft), Tim Weaver (3rd overall supplemental draft) and Marquis White (4th overall supplemental draft) to MLS.

“I think we changed US soccer forever, and we were rewarded for it by MLS picking apart our team. It was horrible for the Seals, but it was a compliment,” expressed Kimtai Simpson.

These were just the players who went to MLS. Many more ended up playing professionally overseas and in South America.

“Back then, MLS had positioned themselves politically in an unholy alliance with the USL that had a one-way beneficiary. We lost nine or our 1997 starters to MLS, A-League and one Belgian first division team. The soccer economy was essentially cannibalistic.”

Kimtai Simpson believes, “small clubs need to be financially rewarded for the players they develop for the MLS. My father spent a lot of money with no return. It’s an unhealthy situation. Just a gesture of a small amount of money would show these clubs that MLS cares.”

Tom Simpson had to say, “My secret agenda was to show that soccer could survive in this country if a solid grass roots, bottom up, approach was taken, (then pointed out that) we ultimately failed because the top down guys held all the cards, essentially funding and the power structure.”

Tom Simpson strongly believed that success could be reached in soccer domestically with a smart financial plan and community involvement.

“If I felt there was a mission it was that if soccer wanted to be successful in this country it needs to start as a grassroots organization and it needs to rise to the top and that’s the model I thought had potential. This top to bottom thing was not the answer. Everyone was failing financially with this top to bottom approach. I believed that soccer did have a chance if you were able to bring it up from within the community and I think I did show that. The part that failed is that there is no structure in place in this country to support that kind of approach. I firmly believe that we are not going to be where we want to be with soccer in this country unless there are more experiences like ours,” Tom argued.

The team was profitable in their first A-League season before being pushed to spend more money by the USL front office.

“In 1998, our first season post the ‘run’ as an A-League team, we survived on a budget of $200,000. No joke,” professed Simpson. “Our revenues were $202,000. The USL guys scoffed at this meager financial success because they constantly prodded us to spend more money even if we didn’t have it. The following year, 1999 we spent $360K, and revenues were $300K. That was the first year we lost money.”

Much of this was due to the move up to the A-League and the change in venue to Kezar Stadium.

“It wasn’t the same when we moved to Kezar. Negoesco was home,” recalled Shane Watkins. “Kezar is

just not a viable venue ,” he added.

When talking to other pro clubs since the Seals in San Francisco, Tom Simpson has said, “The only thing I

can say to you guys is ‘don’t play at Kezar’”.

THE MAGIC OF THE CUP

The Seals are one of the Bay Area and US soccer’s great Open Cup stories. Without the 1997 run many of the Seals players may never have gotten a shot at playing at the next level, whether that be in Europe or in MLS.

“It brings magic to the game and inspiration and that’s what you want out of it,” said Tom Simpson.

“I think the is the only thing that can demonstrate the depth of soccer talent in this country across the different levels. I think it is going to become more and more important, and that more people should focus on it,” said Troya Cowell.

“I just love how the Open Cup is open to everyone,” said Marquis White.

“I love the Open Cup. It’s such a great competition. It can have a huge impact in local communities on growing the game. The run with the Seals was the highlight of my career,” said Shane Watkins. “I really do think that the Open Cup is necessary. If it wasn’t for the Open Cup, the Seals would have never had the experience that we had. It would be nice if every year there was some type of run like that. With the right resources I think I can do the same thing with these SF kids now,” said Shani Simpson.

The Open Cup isn’t perfect yet in the minds of the Seals’ players until stories and clubs like theirs are truly embraced by USSF and the sports world in general.

“If you can put aside the veneer that is created by MLS that somehow they are the best teams in the country, which they have been promoting since 1996, that just isn’t true,” said Troya Cowell on what’s hurting the Open Cup from truly taking off.

“No competition pushes them. It is a huge problem in this country. “It’s the one format that does speak to the issues I’ve talked about, but there is no real follow through because there still is no solution for these teams that start out as grassroots teams to find support once they are successful,” claimed Tom Simpson.

“Our leadership does not know how to integrate this into a process that’s really going to be beneficial to all the people who are really working hard at the grassroots level.”

“The Open Cup plays its role well (in the development of US soccer). It’s a small role but important for teams like us working outside the status quo,” noted Kimtai.

THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY SEALS SINCE 1997 AND THE ACADEMY TODAY

The Seals Academy is still alive today and is predominately focused on youth development and growing the game and no longer has the aspirations to enter the wild west of US professional soccer. Shani Simpson currently does most of the work running the academy, while Tom oversees the club as its ambassador.

“I mostly fight the political battles now, and there are many in youth soccer, and San Francisco is a devastatingly awkward place for anything to do with soccer,” said Tom Simpson.

The Academy has grown to feature 36 teams and more than 300 kids. Shani currently operates an Under-20 and Under-23 club in the NorCal Premier League as well.

“The Seals grew for a reason. People wanted the Seals’ philosophy,” said Shani. “… it turned into 36 teams for a reason.”

The Seals have created a huge number of professional players over the years since the 1997 team as well. Those players include Joe Cannon, Stefan Frei, Wade Barrett, Joe Enochs, Espen Baardsen, Suamy Alvarez, and Calen Carr, just to name a few.

CONCLUSION

The Seals are a soccer club unlike any other past or present in America. They stood for everything American soccer should and could be. They were a community-based club that brought together the best of the diversity the city of San Francisco had to offer. They created a culture and family around the club, from the players to the supporters, built from the grassroots up and not the top down. The Seals were built on an Ajax approach mixed with street ball flair, two approaches that haven’t existed together in US Soccer before or since. The club embodied the spirit of the game, as well as San Francisco, but was torn apart by a system that is not set up to support a project like theirs. This club is everything that US soccer fans dream their club could become. The Seals 1997 US Open Cup run should have been a game changer for the way US soccer operates in several ways. Instead, this massive success story is just another memory. The Seals are the club that every Open Cup fan would have fallen in love with because they represented the absolute best of what the game of soccer is, and can be in the US and the world.